Notebooks

Michael J.W. King

First, if you want to write, you need to keep an honest, unpublishable journal that nobody reads, nobody but you. Where you just put down what you think about life, what you think about things, what you think is fair and what you think is unfair.

This article is written as something of an aid and starting point for writers, about what notebooks are and what they contain. Keeping a notebook can be paralysing without some measure of awareness and encouragement, so it helps first to acquaint ourselves with the space of the page. I hope that this article and others that follow will serve as welcome and practical resources to use that space for your continual benefit. To that end, I'd like to begin with a simple definition and follow in its contours.

Notebooks are the private record of a writer's life, love, and labour. They allow us to remember, to organise, to learn, to practice, to explore, to discover, to justify, to keep, to forget, to keep us honest, to release our valves, to fail on the open page - and help us to navigate lasting success on their spacious waters. They allow, quite simply, anything. And they can contain everything.

Privacy

A private record gives us freedom. A closed space with a constituency of one, notebooks are things we never need share. As such, they foster honest expression with a welcome gentleness, without judgement. Privacy with a notebook also means we don't need to filter or think about neatness in appearance or language. And certainly, there is no expectation of success nor any repercussion of failure. There is room to experiment and hash something out. We can get things wrong and get things right, quite freely. Imagine an athlete at a closed off arena for their practice. They may practice for hours, repeating a set of events for a competition. They may trip and fall and curse. They will fail - that's why they're practicing. But the hours go on, and the athlete goes on going on. By the time the competition comes round, the crowd sees their event and - God willing - their triumph. They'll never see the practice. They may know of it and give a nod of support to the catalogue of hours, warm ups, variations, failures, eventual layers of success that the athlete accumulates in that arena, but that is not for the crowd. The arena and those countless private hours are for the athlete only, along with all its struggles and consolations. The same is true of you and your notebooks. It is a private arena, a closed and sacred space not only to record but also to create your entries. As Susan Sontag declares:

In the journal I do not just express myself more openly than I could do to any person; I create myself. The journal is a vehicle for my sense of selfhood. It represents me as emotionally and spiritually independent. Therefore (alas) it does not simply record my actual, daily life but rather - in many cases - offers an alternative to it.

Entries

Entries are the defining, elementary unit of a notebook. Although the common building block, they vary among writers in their content, layout, and nuance. Some writers kept their entries as a raw and scattered depository of fragments, thoughts, sketches. Others kept a diary or a more traditional journal, recording their day and their day's reflections, scribbling any overheard conversation they found interesting, and noting what they saw around them in their own words. Entries like these may be embryonic of personal essays, with a writer taking and expanding them, investigating them while keeping an intimacy and honesty of thought and being. Others still kept a notebook much like an artist would a sketchbook, filling pages with sketched drafts and experiments with sentences, prose, and poetry.

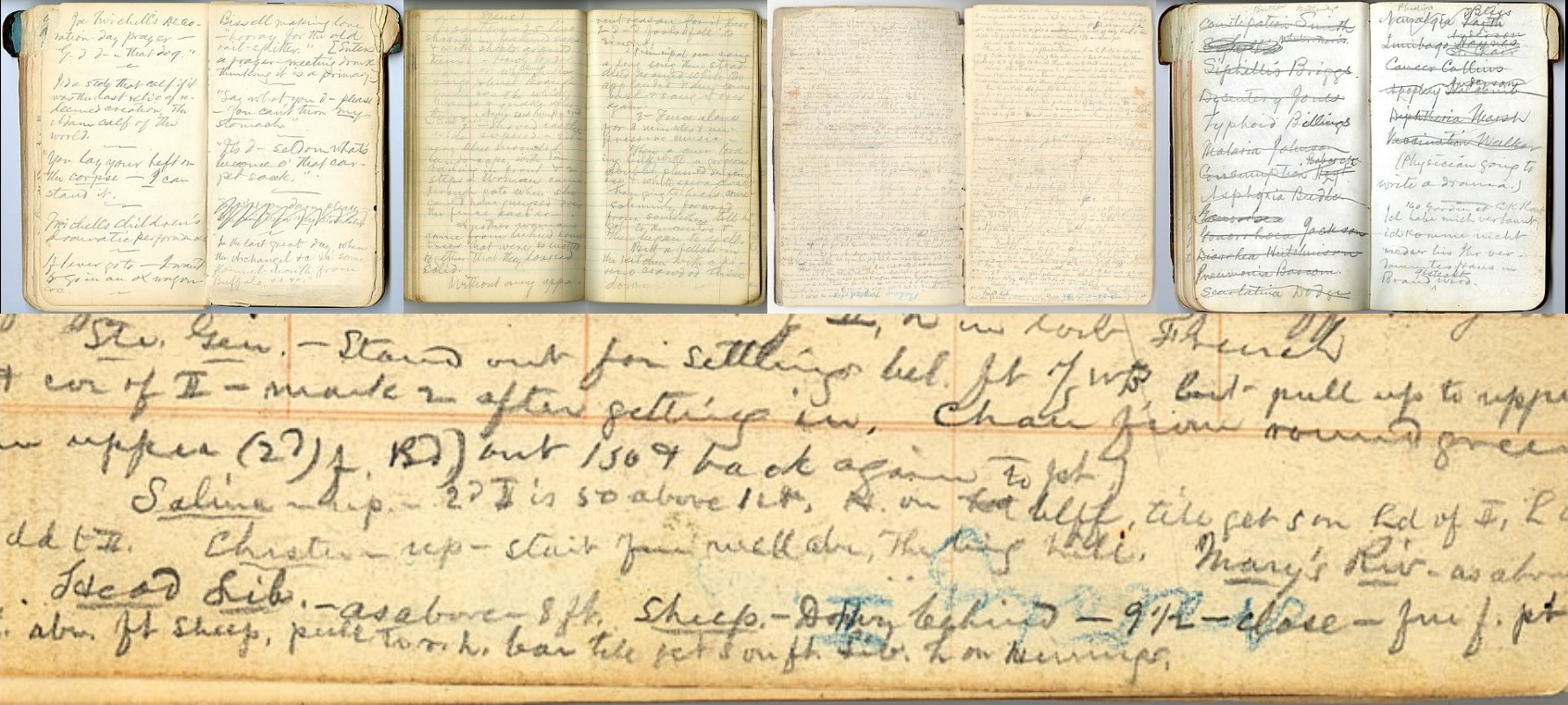

All of these are good. All of these could be yours. They each have their uses, their own moods and tones, and it helps to be open to possibilities. I want to present a small catalogue of entries from the notebooks of various writers to give you a feel for what goes on behind the scenes. These have either been published or are of public and historical interest. As such, they are readily available in one form or another for further exploration. I encourage wide and varied reading of published notebooks and diaries of writers; they gift as much courage and comfort as inspiration and insight. Below is a small imagequilt of the notebooks of Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), illustrating diversity even from a single writer.

Going clockwise from the top left, we begin with a series of sketched anecdotes separated by a short line. Some of them may have been expanded into something more literary, but not all of them. And all of them can be hoarded and kept, forever banked and saved. Next, we have a sketch of Clemens' own take of Verdi's Il Trovatore, made after attending a performance in San Francisco. Third is filled with more technical entries, crammed with details on the Mississippi river during his training as a cub pilot. Fourth, at the top right, are scribbles and sketches of possible names of characters for a play. The bottom image spanning the width of the quilt is taken from the same technical river notebook previously mentioned.

© 2010 The Regents

of the University of California. Image courtesy of The Bancroft

Library, Mark Twain Papers and Project Collection. Used with

permission. Source page can be

found at this link. Famously, Clemens also kept

notebooks of his own design. They were small enough to be kept with

him and littered with practical idiosyncrasy: each notebook had his

pen name on the cover, the tabbed protrusion on the top right allowed

Clemens to tear off each page as it was filled so as to always mark

where he was, and the pages were plain rather than lined. His

notebooks remained both a companion to him and a record of entries

both considerable and trivial, including:

business notes, addresses, personal errands, literary ideas ... [as well as] seven pages of his notebook with a list of potential characters, including "Rectum Jones" and "Scrofula St. Augustine."

And companions they often are. Kept in the pocket or bag or stored in a warm drawer at a desk, notebooks are lifelines for many writers. They become confessionals, dear friends. They are also an extension of their own thinking. Beethoven, for example, carried a pocket notebook with him on his walks "just in case" (rarely without one, in fact; he is often depicted in art with a notebook), and often sketched the beginnings of his musical compositions as much as personal thoughts and maxims. Discoveries during writing can be jotted down, and our notebooks turn into a kind of hand-beaten railroad which documents our own journey through our tasks. One example comes from John Steinbeck during a prolific period between June and October 1938, where he kept a journal alongside composing Grapes of Wrath. Here, at the beginning, Steinbeck set his goals, noted some observations and reflections of his day while casting reminders for how the novel must go, all scribed on a financial ledger:

![Autograph journal : [California], 1938 Feb. - 1941 Jan. 30.](https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/literary/steinbeck_ma4684.jpg)

Here is a transcription of the entry dated June 1st: The full journals during his time writing Grapes of Wrath are published and readily available as Working Days: The Journals of 'Grapes of Wrath'.

To work at 10:30. Minimum of two pages. Duke expected today making it not so good. Yesterday turtle episode which satisfies me in a number of ways. Today's project - Joad's walk down the road and meeting with the minister. Dinner tonight at Pauls' with Rays along. Day is over. Finished my two pages. I think pretty well. Casy the preacher must be strongly developed as a thoughtful, well-rounded character. Must show quickly the developing of a questing mind and a developing leadership. Duke not here yet. Tomorrow must begin relationship between these men.

Such journal entries become, quite naturally,

diaries.

All day, David wants to know, "When do you die in your

sleep" (after I recited the bedtime prayer, Now I lay me..., to

him this morning).

We've been discussing the soul.

-

Susan Sontag, from Reborn: Early Diaries 1947 -

1964, November 1st, 1956.

A diary entry can be practically defined as a record of the

events and thoughts of the day that involve the writer. We may keep a

book consecrated to these types of entries, or they may slot alongside

other kinds. Sentence neatness or style is secondary: note Steinbeck's

more fragmented, short sentences - a turn from his more considered and

varied prose. By alternate measures, the comedian and presenter

Michael Palin - an avid diarist since he was 25 - is typically more

grounded as he recounts his day compared to the high surreal energy of

his Monty Python pedigree:

To bring us back to reality with a bump, we watched the first of the new Monty Python series to be shown in the States. It was the 'Scott of the Antarctic', 'Fish Licence', 'Long John Silvers v. Gynaecologists' programme. Strange how many of its items have become legendary, and yet looking at them, TJ and I were amazed and a little embarrassed at how very badly shot everything was. Ian really has improved but judging by that show, he needed to. Was this really the greatest comedy series ever? Steve slept through it.

It's not just the day's events and thoughts that are worthy of expression. Alongside the What and How and Why of a When in a diary sits the Where. A good writing practice is putting down what we notice around us, as it sharpens our observation and our skill at selecting details for enchancing the life, variety, and truth of our prose. Here, in an evocative passage of description, Lady Murasaki opens her diary for us:

As autumn advances, the Tsuchimikado mansion looks unutterably beautiful. Every branch on every tree by the lake and each tuft of grass on the banks of the stream takes on its own particular colour, which is then intensified by the evening light. The voices in ceaseless recitation of sutras are all the more impressive as they continue throughout the night; in the slowly cooling breeze it is difficult to distinguish them from the endless murmur of the stream.

Diary entries like these give us space not only to observe and

remember and plan, but also to open up. We can be messy and let our

hair down. They give us time to reflect and ask questions about our

day. Our thoughts, feelings, and perceptions are rightly invaluable to

us, and making a habit of getting them down on paper serves as a

lifelong whetstone for our own writing ability. If nothing else, it

keeps us honest.

But what is more to the point is my belief that the habit of writing

thus for my own eye only is good practice. It loosens the

ligaments.

- Virginia Woolf, from A Writer's

Diary, April 20th, 1919. Mariner Books, 2003.

But of course, notebooks are not only diaries weaved with passages of

idiosyncratic time. They are also fragmented, haphazard, broken

things. And no less precious for it. A heartfelt dash or an unusual list

remains vivifying and interesting. Clemens' notebooks above was one

example of the freedom of scribbling something down. Here are two more

examples, this time from women an age and ocean apart - Marilyn Monroe

and Sei Shonagon - to give us a timeless glimpse into their all-too

finite lives: Sei

Shonagon depicted with her diary,

via Wikimedia Commons.

Sei

Shonagon depicted with her diary,

via Wikimedia Commons.

Make no more promises make no more explanations - if possible. Regarding Anne Karger after this make no commitments or tie myself down to engagements in future - to save not being able to keep them and mostly to avoid feeling guilty which is now the case.

Things with far to go - The work of twisting up the long cord of a hanpi jacket.

Someone crossing the Osaka Barrier just beyond the capital, setting out for distant Michinoku.

A newborn child, at the start of the long journey to adulthood.

We never need hide ourselves from our notebooks; they may be the only place we can go to. The pages in turn act as the resin that holds together our broken phrases and thoughts; our journeying minds and hearts.

Finally, sketches. Some of the most exciting glimpses into a writer's life comes from the raw material of their work. The attempts and scribbles of great writers reassure us that nothing well written was ever written once. Here, in one example, William Blake's notebook from c.1787 provides a look into his revision and composition process, trying stanzas out, amending them, scribbling here and there the words that might work and, in the end, feel inevitable:

Images used under fair use and are in the public domain, and

are taken from The British Library online collection, item

entitled The Notebook of William Blake (the 'Rosetti

Manuscript') Shelfmark Add MS 49460.

Images used under fair use and are in the public domain, and

are taken from The British Library online collection, item

entitled The Notebook of William Blake (the 'Rosetti

Manuscript') Shelfmark Add MS 49460.

The entire notebook is worth a browse, accessed by clicking on any of the images or the link underlined in the attribution. As the sidebar description from the British Library states, it allows us "to follow the genesis of some of his best-known work, including 'London', 'The Tyger' and 'The Chimney Sweeper'." And it's not just poets and novelists that are included in the running mess of sketching their writing. Thomas Edison kept technical notes, drafts of essays, telegrams, letters, journals. He even blotted and scrawled the odd ink test:

Citations going clockwise from top left:

Citations going clockwise from top left:“Technical Note, John F Ott, June 8th, 1886,” Edison Papers Digital Edition, accessed August 28, 2018, http://edisondigital.rutgers.edu/document/X128B053.

“Technical Note, Charles Batchelor, Ezra Torrance Gilliland, James Adams, Thomas Alva Edison, May 31st, 1875,” Edison Papers Digital Edition, accessed November 16, 2020, http://edisondigital.rutgers.edu/document/NE1676229.

“Essay, Thomas Alva Edison, 1891,” Edison Papers Digital Edition, accessed August 28, 2018, http://edisondigital.rutgers.edu/document/PA035.

Images used with permission. Provided by The Thomas Edison Papers at Rutgers University.

It must be said that while all the examples highlight variety and demonstrate some of the myriad ways in which we can keep our own entries, they do not do justice to the full works from which I have cited. I once more encourage following up on interested sources of quoted passages, and experiment with what resonates as you read. Sei Shonagon, like her contemporary, Lady Murasaki, is varied in her style of entries at a time when private prose was something protean in content and form during Heian-era Japan. She is judgmental, at times funny, but always entertaining. Marilyn Monroe composed poems and kept notes on acting craft, and every entry speaks of a sensitive, insightful woman always at odds with her personal demons. Michael Palin carries a warm, sober air throughout, and the tension felt during important times in his life is real on the page, even if history has already unfolded the outcome. And this is to say nothing of the giants of notebook-keepers: Virginia Woolf, Franz Kafka, Eugene Delacroix, George Orwell, among countless others.

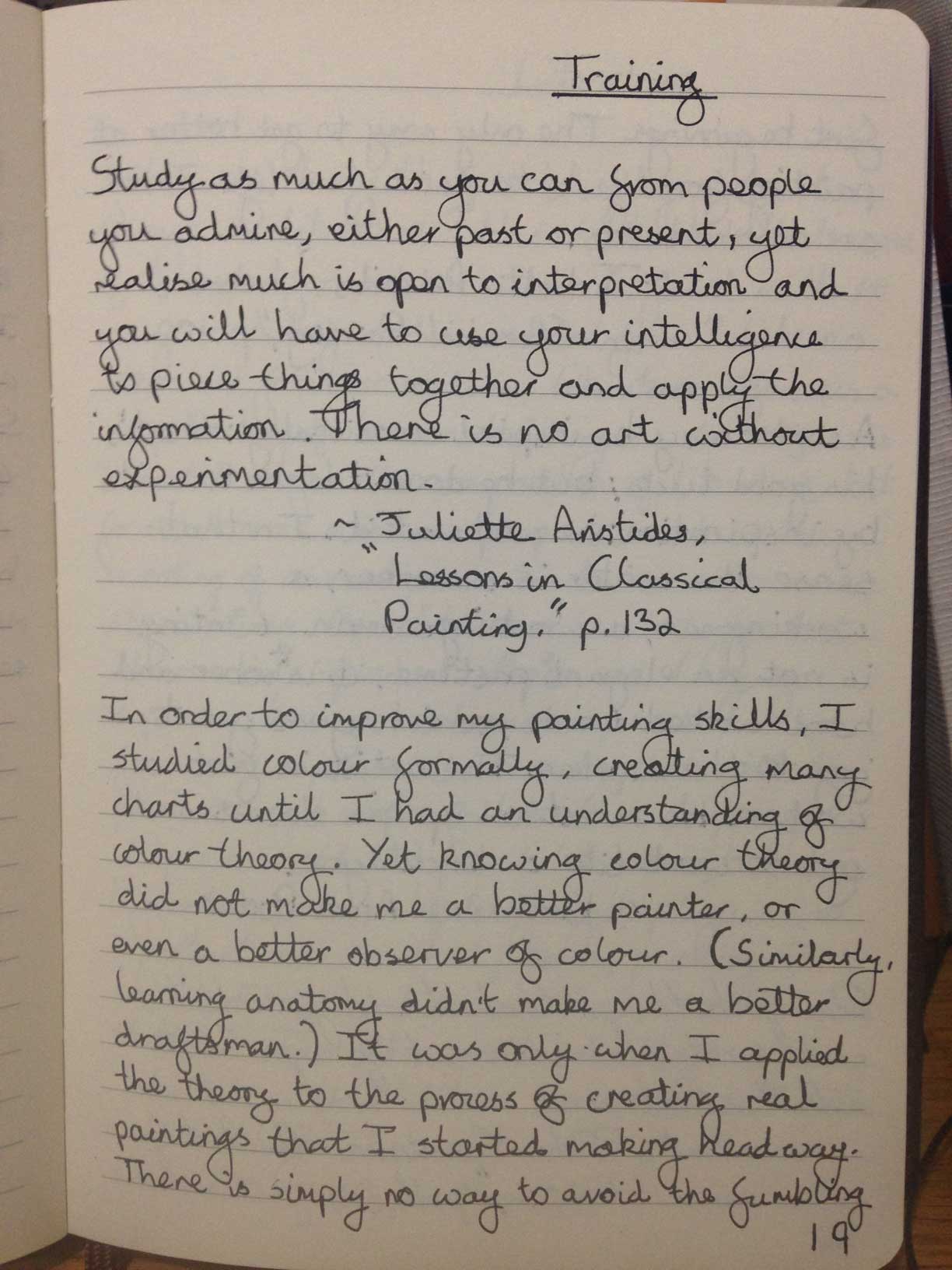

Organisation

Much like individual entries, how we organise our notebooks is a matter of taste and temperament. A little bit of consideration goes a long way to keeping them clear for future reference. Annie Dillard kept her journals indexed, and over the years they grew to include something of a bespoke encyclopedia informed by her wide reading:

I began the journals five or six years after college, finding myself highly trained for taking notes and for little else. Now I have thirty-some journal volumes, all indexed. If I want to write about arctic exploration, say, or star chemistry, or monasticism, I can find masses of pertinent data under that topic. And if I browse I can often find images from other fields that may fit into what I'm writing, if only as metaphor or simile. It's terrific having all these materials handy. It saves and makes available all those years of reading. Otherwise, I'd forget everything, and life wouldn't accumulate, but merely pass.

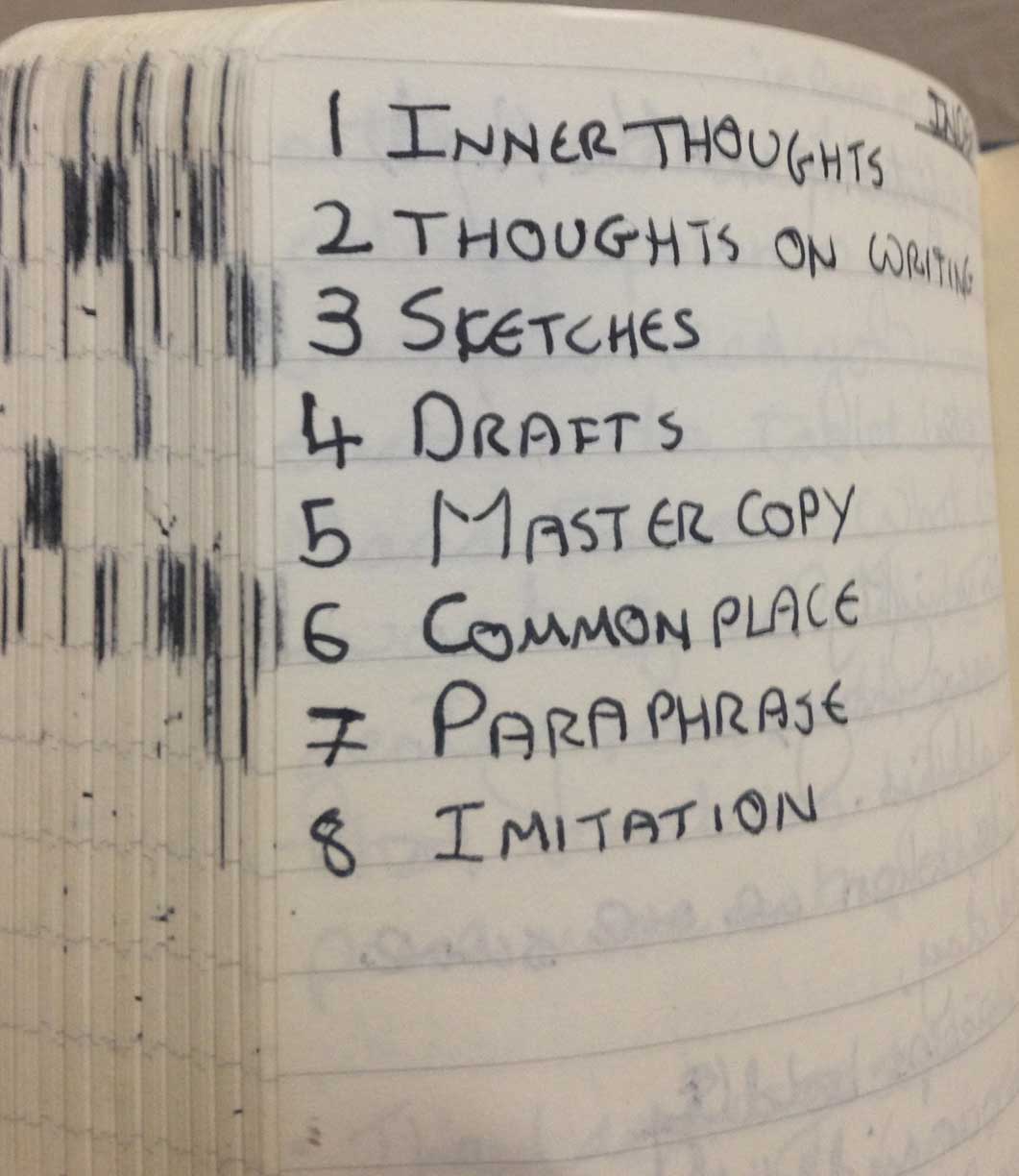

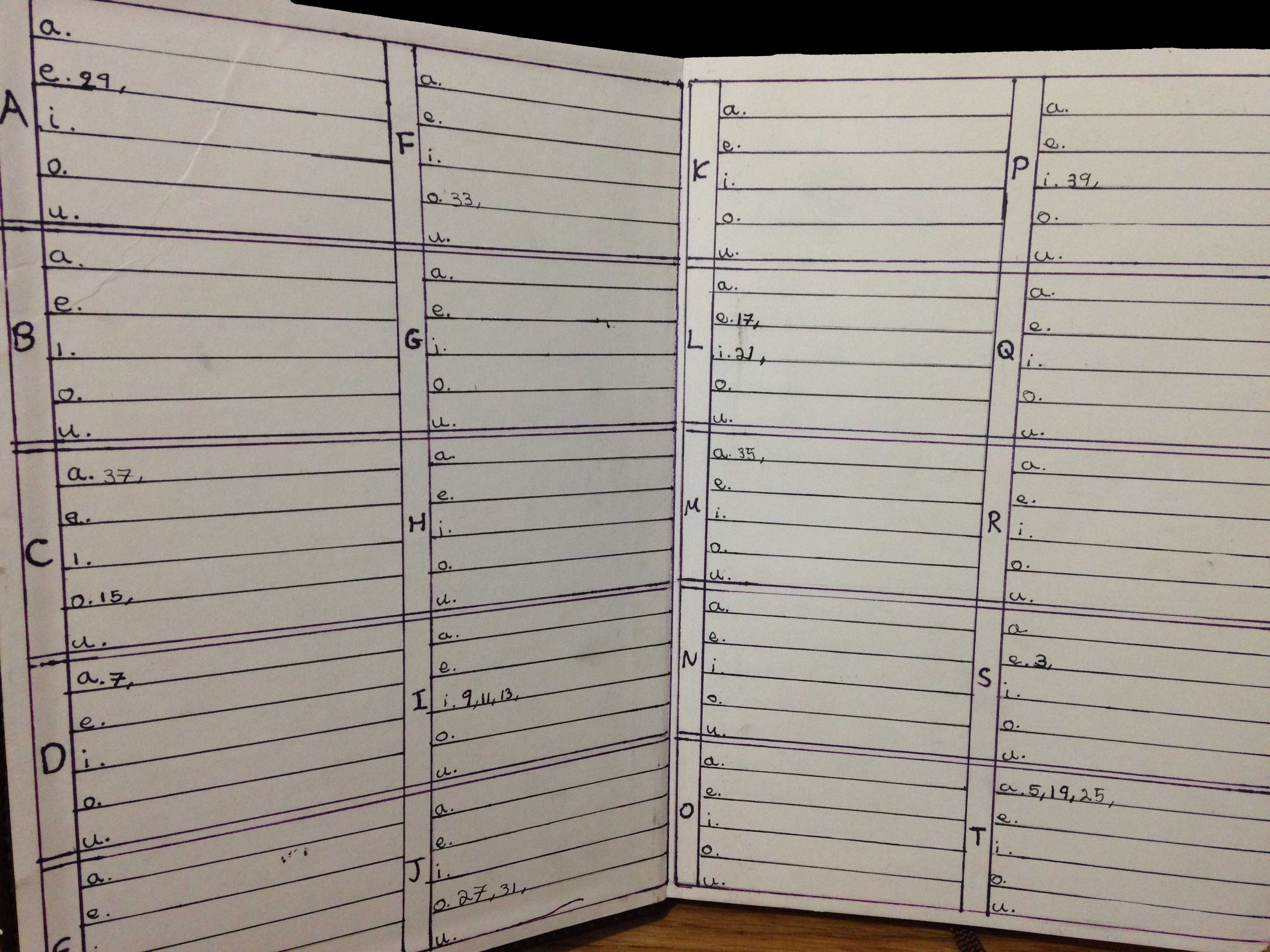

An

example tabbed index page with a series of entries and relevant pages

tabbed.One way to index is to tab the edges of your notebooks as

you fill them after setting up the back page with topics or styles of

entry to refer to later. Each line becomes a space for a new entry, and

if you run out of lines, you can column-up beside it with a different

colour.

An

example tabbed index page with a series of entries and relevant pages

tabbed.One way to index is to tab the edges of your notebooks as

you fill them after setting up the back page with topics or styles of

entry to refer to later. Each line becomes a space for a new entry, and

if you run out of lines, you can column-up beside it with a different

colour.

Diary entries are, of course, organised by date. Sometimes that's all we need. Such a simple organising principle invites diversity in our entries, and is perfectly suited to when we are journeying or documenting change over a period. Over time, the completed notebooks become a powerful reminder when kept together. This becomes explicit with travel or expedition diaries where coherence is set not just to a span of time but also to location. The Lewis and Clark journals, Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London, and Basho's The Narrow Road to the Deep North are all exemplary and classic examples. As always, seek and discover not just these but also others. Below are some striking visual pages from Kolby Kirk's trail on the Pacific Crest:

© 2011 thehikeguy.com. Used with permission.

Another consideration when organising your notebooks is to keep more than one of them at a time. Three, to be exact: a notebook, a commonplace book, a daybook. One for your labour, one for your love, one for your life. Three books, clearly demarcated, define the value of one. Notebooks, I trust, need no further definition. Likewise, a daybook is a planner, perfectly suited for administration by setting out schedules and lists, capturing dashes and reminders, and for holding the big picture. Any kind of entry that's locked to time and in need of quick reference can find its place in a daybook.

Commonplace books are a little different.Commonplace books receive their name from classical rhetoric where, as an aid to memory, practiced speakers would keep a compilation of stock arguments to use in speeches involving common (general) topics such as tyranny or a war hero. These arguments had the advantage of universal application rather than dependence on a specific case. Over the centuries, the practice of keeping a "book of commonplaces" transformed into a practical and scholarly pursuit by people seeking to store knowledge of their craft and interest. They are more of a construction, a net you build to catch quotations and short extracts from sources you then organise under topical headings. In days gone past, you could purchase already filled commonplace books, compiled from sources taken from poetry and other humanist literature. You could also buy formatted copies of Shakespeare and the plays of Johnson. These versions had designated commonplace markers and passages pre-quoted for you to copy down in your own book. Yet while the raw material for the practice of commonplacing grew in abundance, setting up a commonplace book itself remained something less formalised. However, there are resources online based on a popular method invented by John Locke which I'd like to link below:

Structuring a Commonplace Book (John Locke Method) by Thomas Burgess. This is a short and practical article on how the index is constructed and filled in, as well as how entries are made as you go.

A new method of making common-place-books by John Locke. Harvard Library Viewer has uploaded a scanned version of his essay as a digital archive.

Indexing commonplace books: John Locke's method by Alan Walker. This is a link to a PDF article which gives an informatve analysis of Locke's method, as well as an overview of the tradition of commonplacing.

Many, many other methods exist. We may keep them loose-leaf, binding them at a later date ourselves. We may keep them entirely on the computer, meticulously indexed, referenced and cross-referenced; or we may power through bound notebook after bound notebook, barely keeping track of what goes where. There is no wrong answer, and our answers may change as the years accumulate and the occasions present themselves. At the outset, any lasting or comfortable architecture to hold your thoughts on paper does not matter as much as taking the first step to simply get it down and out onto the page. Take the risk to go in unprepared, discovering as you go; write often and grow your collection of entries. From there, you can find the appropriate means to keep them all together for future reading.

Epilogue

My thanks go to the sources listed above for their kind permission for me to use their work in this (now long-overdue) article, and for the information at Tufte CSS.